A strange black light…

Sway by Zachary Lazar

It’s just that demon life has got you in its sway. (M. Jagger/K. Richards, 1971)

It’s become conventional wisdom to accept the notion that the 60’s officially ended at Altamont—the free concert near San Francisco in December of 1969 that resulted in the deaths of at least four people. In Zachary Lazar’s wildly creative novel Sway, any bright flowering of peace, love and positive creativity hardly happened; the Beatles, not mentioned by name, are just “a band from Liverpool, of all places.”

Lazar has twisted (woven is probably not the right word) three tales in a dark braid, threads sometimes intersecting but mostly not; a purely fictional, speculative narration of the early days through the zenith of the Rolling Stones; a tale of Bobby Beausoleil, a young man fatally under the influence of Charles Manson in the brown grassy hills of southern California; and the tormented underground filmmaker Kenneth Anger. Lazar has found a way to shine a strange, new black light on this decade, a still festering contemporary heart of darkness (or light, depending on your point of view) that won’t go away. With little and non-descript dialogue, minimal plot and not much characterization, it is the novel’s visuality; its attention to the sensual details of the depiction of music in both its creation and its performance, and the novel’s strong sense of place that make Sway a remarkable success.

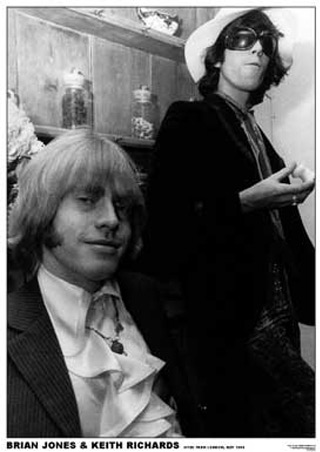

The early Stones, like any garage band, have an endearing clunkiness, making it up as they go. Lazar shows an image that is a far cry from fan club hagiography. This is no guitar hero;

“Onstage, they are all awkward, all except Brian. His face is almost feminine, pale and wide-lipped, but his hands are large, blocklike, and they handle the guitar like a shovel. He attacks the strings with wide up and down sweeps of the wrist, forms the chords with wide stretched fingers, making his playing look more difficult than it is.”

Guitar players have always been interested in making it look difficult—girls are impressed. But the Stones seem to have to fight there way out of every gig, tough joints in working class England.

The song Sympathy for the Devil , Lucifer making his pitch, is one of the novel’s central motifs. Recorded in early June 1968, just as Bobby Kennedy was assassinated, the description of its transformation from a few simple chords to finished masterpiece;

“It would take them three nights to put the song into its finished form. In those three nights, it would change from a folk song to a psychedelic song to a soul song, and then emerge something raw and percussive, like the voodoo music of Haiti….It would start with a yelp, a monkey screech, and a flat patter of bongos, a resonant thud of conga drums, a locust-like hiss of maracas. It would become a wild celebration of everything it had started out lamenting.”

The song predates MTV, of course. And it is a tune one may have heard hundreds of times, perhaps even performed it, but Lazar’s account of its percussive hoots, hollers, screeches and voodoo-hoodoo drives a mental picture that is indelible.

Rock and roll is visceral in nature, its thumping of a bass in the gut felt even in the cheap seats of Madison Square Garden. Lazar nails it;

“It was a series of vibrations amplified through electric circuits, a current of sound the crowd could feel on the skin beneath their hair, in the cavities of their chests, in their rectums and their groins. It registered in their bodies, in the pulse of the blood, but also in their minds, the part that was always changing as senseless and illogical as a dream.”

The sensual, visual choice of words—cavities, chests, rectums, groins and blood—strong, uncomfortable and sexual—are hardwired in this music, this voodoo gumbo of rock and roll—enough to make any parent uneasy.

Lazar makes economic but effective use of poetic devices. His alliterative word selections are worthy of Cavafy and his Alexandria, presenting a vivid image of Marrakech—earth, eggshell, electric, souks, scraped, sand and city, burned, busier and bright;

“He had lost Tom Keylock somewhere in the fabric souks a few hours ago and now he was looking through the window of the cab, at the dense wedges of building, earth-colored or eggshell-colored, which appeared as if they’d been scraped together out of sand. A few electric lights burned like flares along the busier streets, bright orange or neon green. They made the city of Marrakech look more and not less ancient.”

Marrakech is foreign, alien and indeed ancient—far from Keith Richards’ mental map of America. For him, America was foreign, but familiar, young and romantic. He studied an actual map as a kid, memorizing “the shaded areas of their mountain ranges, the pale blue contours of their shorelines and lakes…He knew it was out there, a physical reality, not a dream. He had the maps, the names, the border and geography.” He was in love with a place he’d never seen. So he and his friend Mick internalize that map, synthesize the music of the records they find, painstakingly move the needles back and forth over the black grooves and produce Sympathy For the Devil, a song that becomes one of the symbols of their coming-of-age decade. “The decade will pass, forty years will pass, and maybe you’ll hear a snatch of it through a car window, the sound of it still a surprise over a stranger’s radio, the old song sent around the planet in waves that never end.”

That time still has us in its sway. And Sway makes us see it.

Sounds like a winner. Care to start a list of best fiction about rock and roll and/or pop and country? This sounds fantastic, based on your description. One overlooked book out there is “Lost Highway” by Richard Currey. The opening paragraph is just worth writing down.

“The road in front of me, and the night: the arbored highway a friend of sorts, passage and movement that shape the hours into something a man might accept as recognizable. In this country it is a kingdom of trees and low mountain, shadows that trace the rim of night, the road out of Nashville, cut rock and slate-face as I move uphill into darkness. I will drive toward daylight, east to Knoxville before turning north, into the Cumberlands and Kentucky.”

Great book !

What is it about the road, the “arbored highway” that is so fascinating? It’s Kerouacian, it’s Rip This Joint, it’s a love letter to the map of America.

Good idea…a source list of fiction and rock ‘n roll. There’s another Lost Highway, by Peter Guralnick, but it’s not a novel…great sourcebook on the roots of r & r.

Thanks for the tip on Currey.